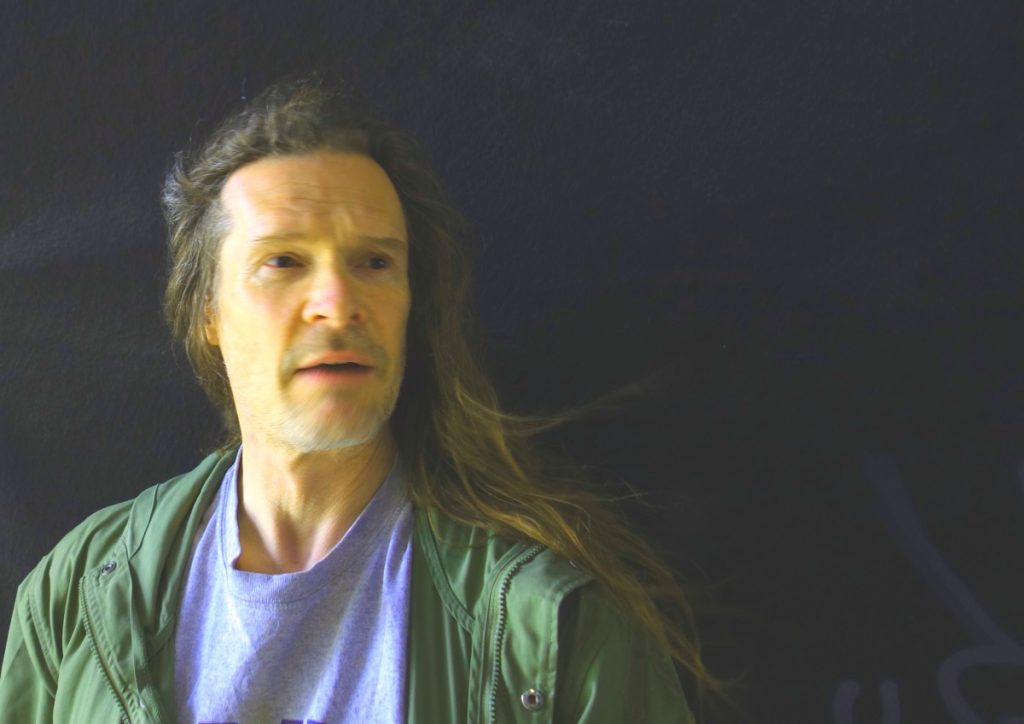

Text och bild: Staffan Castegren

När första världskriget bröt ut flockades Europas medborgare till rekryteringskontoren. Pressen spred lögner både om fiendernas ondska och om det egna landets godhet. Många upplevde kriget som ett äventyr, som ett mandomsprov, som en nationell rening. Detta gick dock över mycket fort. Snart insåg de flesta att det enda som händer i krig är att fattiga människor dödar varandra och att en liten grupp rika människor blir ännu rikare.

Efter 1918 var det folk som sade att det här var kriget som skulle göra slut på alla krig. Men så blev det inte, som vi vet. Men varför fortsätter mänskligheten att kriga? Det är väl rimligt att anta att en överväldigande majoritet av jordens befolkning helst vill slippa det fasansfulla valet att döda eller att dödas. Det enda rätta, då som nu måste vara att kämpa för freden.

Min tro är att kriget som idé växte fram samtidigt som klassamhället för ca 12 000 år sedan. Det vill säga när mänskligheten slog sig på jordbruk och började producera överskott. För det är ju så att om det finns ett överskott, så finns det alltid folk som anser sig ha rätt att bestämma över det. En elit växte fram som med våld och list tryckte ner majoritetens berättigade missnöje.

Våldet och listen sköttes av soldater och präster vars första uppgift var att kuva det egna folket. Senare kunde man vända sig mot andra grupper av människor och då växte det ledande skiktet med nya funktioner, eliten behövde bland annat konstnärer och historieberättare. Många tidiga bildfriser och texter handlar om mäktiga kungar som dödar och stympar oräkneliga fiendesoldater.

Och så här fortsatte det genom historien. Religionerna avlöste varandra, taktiken på slagfälten och vapnen utvecklades och med tryckkonstens hjälp kunde lögnerna spridas allt effektivare. Men grundidén var densamma: Det var eliten som önskade krigen, inte minst för att befästa sin egen makt. Kanske riktar sig alla krig egentligen i första hand mot det egna folket.

Situationen i dag är sig rätt lik. Religionen är på tillbakagång, men otaliga filmer, som till exempel Star Wars och Sagan om ringen bedriver en skamlös krigshets. Där är alla fiender demoner, men alla som dör på den rätta sidan kan räkna med ett liv efter detta. I dag drar eliten in ofattbara förmögenheter på sin krigsindustri och medierna sprider villigt sina ägares åsikter om krigets oundviklighet.

Putin och den ryska eliten har naturligtvis en odiskutabel skuld till kriget i Ukraina. Men allt måste sättas i en historisk kontext. USA har sedan 1945 bedrivit en oerhört aggressiv utrikespolitik. Landet har i princip varit i krig oavbrutet sedan dess och deras militärbaser är spridda tätt över jordens yta. Men trots alla miljoner som dött i deras krig, tycker i princip alla medier och politiker i väst att det är ett acceptabelt förhållande.

Ryssarna upplever dock detta som ett hot och när nu nätet av Nato-baser dras åt ytterligare växer både deras rädsla och deras motstånd. Aggressivitet väcker alltid aggressivitet. När nu alla västländer okritiskt ställer sig på USA:s sida känner de sig sannolikt alltmer trängda. Krigshetsen i våra medier har ju pågått i månader och nu verkar det svårt ens för de klokaste att tänka sansat.

Sverige har inte skickat vapen till krigförande nation sedan finska vinterkriget. Men nu är det tydligen dags igen. Medierna fylls av så kallade experter som säger att även Sverige är utsatt för krigshot. Och i riksdagen sprider sig populismen som Corona. Alla vill överträffa varandra i hårdförhet. Ingen säger att kejsaren är naken. Mediedrevet har fått opinionen att svänga från alliansfrihet till Nato-anslutning.

Situationen i riksdagen är verkligen häpnadsväckande: Arbetarpartierna anser att arbetarna ska gå ut och döda varandra igen i elitens krig, miljöpartiet tror att krig är bra för miljön, det kristna partiet tycker att bergspredikan bara är skitprat. Det är egentligen bara de blåbruna partierna som är som vanligt, deras grundidé har ju alltid varit att miljardärerna ska få ännu fler miljarder.

Vad var det som startade första världskriget, Agadirkuppen 1911, skotten i Sarajevo? Därom tvista de lärde. Men situationen då är skrämmande lik dagens läge. Den totala aningslösheten, likriktningen, där alla springer åt samma håll, upprustningen, det öronbedövande vapenskramlet i alla medier. Ska Ukraina 2022 bli en ny symbol i historien tillsammans med skotten i Sarajevo 1914 och inmarschen i Polen 1945?

Vi måste säga nej till Rysslands krig, men också till USA:s världsherravälde. Vi måste säga nej till upprustningen överallt i världen. Vi måste få bort kärnvapenhotet. Nej till resursslöseriet och miljöförstöringen, nej till den groteska ojämlikheten. Ska vi lyckas lösa jordklotets akuta problem måste vi fokusera och jobba tillsammans. Vi har faktiskt inte tid med den här skiten.